Leadership is vital to successful workplaces, but more can be done to ensure the best and most diverse leadership is developed in New Zealand.

These are among the key findings from the first phase of Te Manu Arataki Leadership Project, a collaborative Ohu Ahumahi workforce development council (WDC) project led by Ringa Hora to ensure New Zealand workplaces have the best opportunities to nurture leaders at all levels.

As part of the project team’s look into whether existing leadership development and credentials are fit for purpose, an environmental scan was undertaken asking some fundamental questions:

- What is leadership?

- Why is leadership important?

- How are leaders developed in Aotearoa?

- What are the barriers and enablers in leadership development?

What is leadership?

Leadership can mean many things. In a workplace, it’s seen as responsibly guiding people in a clear direction, making decisions for the good of the team and the organisation. But it’s increasingly seen as more than just being exercised by managers, executives, or team leaders.

Workplaces benefit from leadership at all levels. People can be effective leaders of an organisation, of a smaller group, and even of themselves. There is often a focus on people with formal responsibilities, such as team leaders or those in higher management and governance positions. However, a more inclusive view recognises the ‘everyday leadership’ that people display in the way they turn up and conduct themselves regardless of their role or hierarchy – for example, by making good decisions, taking initiative, having the confidence to speak up especially on integrity matters, and being a model in their work. The skills, knowledge, and attributes that people develop and demonstrate at one level provide a foundation to build on in others.

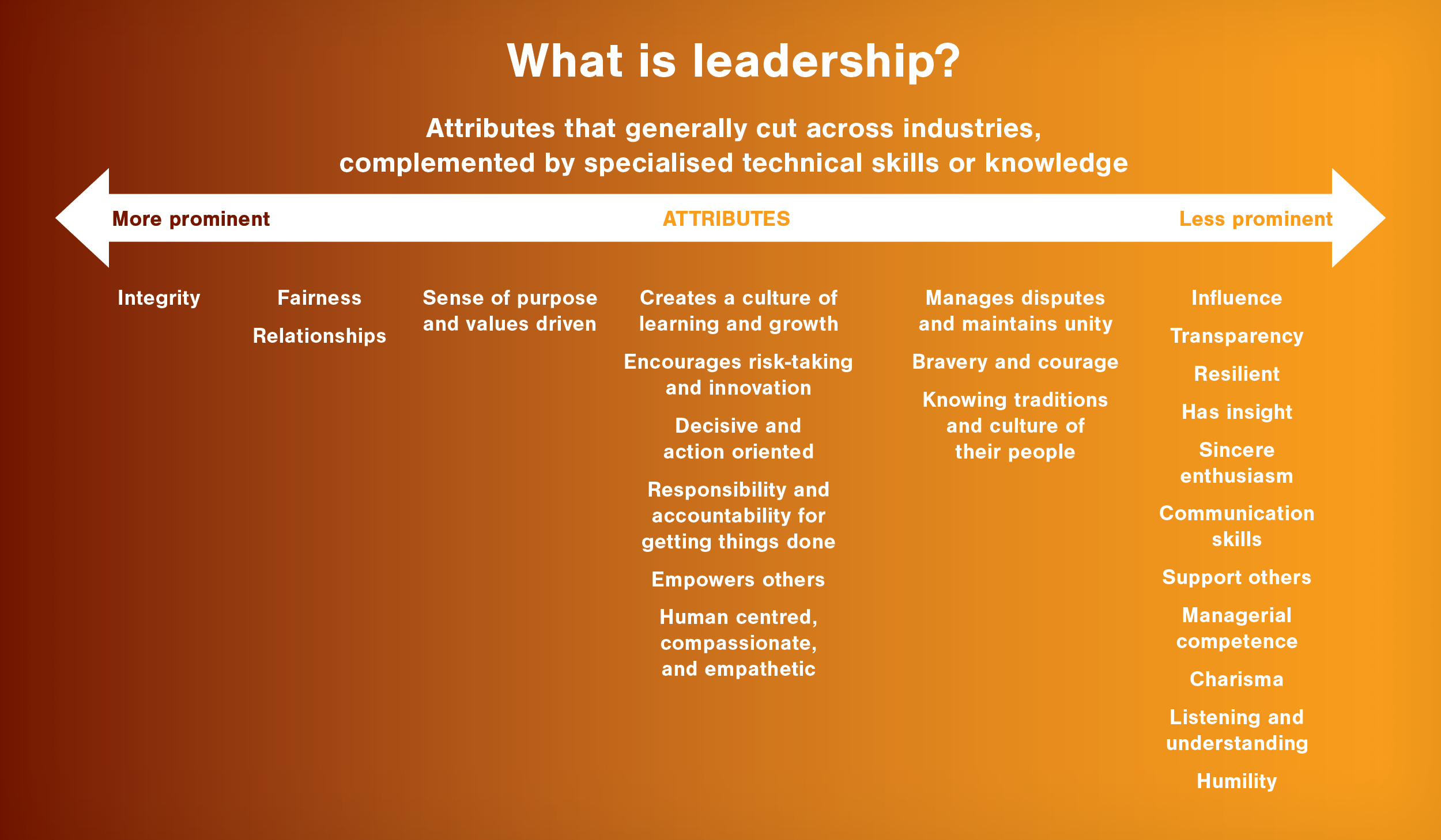

Though some industry-specific knowledge and skills are seen as important for leaders, there are several attributes seen as important for a good leader in a generic sense. Some of the most prominent include integrity, fairness, relationship building, and a sense of purpose driven by strong values. For Māori, leaders are guided by tikanga as well as having inter-generational and multi-faceted priorities. For Pacific people, the heart of leadership is a spirit of service and Pacific values.

Why is leadership important?

Good leaders can help improve productivity, performance, and impact.

But leadership is also important in a community sense, for wellbeing reasons. Its success generates wider economic, social, and employment benefits, and provides the vision and wisdom to meet future challenges like technological innovation and climate change.

Empowering people from these groups as leaders and employees within their communities or in the wider economy helps workplaces reach their fullest potential.

How are leaders developed in Aotearoa?

There is an extensive range of ways to learn leadership skills; some may be credentialised and recognised on the New Zealand Qualifications and Credentials Framework, but many are not and rely on informal or in-house recognition.

A range of organisations have developed their own training or leverage off existing offerings, whether they’re developed locally or internationally. We have found various examples across iwi, regional development agencies, peak bodies, community groups, advocacyand membership organisations, and employers.

Many non-credentialised options are short and online, focusing on selected skills, knowledge, or attributes to meet specific needs. In some cases, there is a pathway to progress in the complexity or range of leadership skills, while in others the training opportunities are a standalone offering and not part of a coherent package.The financial cost varies greatly and this is met by different public and private arrangements. We have seen examples of low-to-no fees options offered by community, advocacy organisations, and regional economic development agencies.

There are a range of targeted or tailored opportunities for different communities, with many of these either developed by, or at least in partnership with, the particular group they serve. Some of these are in response to a general recognition that mainstream options don’t reflect the needs and aspirations of particular communities, whether that’s women, migrants and refugees, or other cultural groups. Others have been developed to reflect the demographic characteristics of the region or industry in which they’re based (for example, a large population of Pacific people in Tāmaki Makaurau has seen the development of Pacific-focused opportunities albeit pan-industry). The scale or reach of these options is sometimes unclear; meaning we don’t know the extent to which the specific need is met.

On-going mentoring arrangements also enhance leadership development by increasing the visibility of different communities in leadership positions and enabling access to wider supportive networks. They provide reciprocal value for mentors and mentees – with the chance for people to learn from others and vice versa to support others in their development. Mentoring was particularly valued when the relationship is between people with similar experiences – for example that may include shared cultural, gender, or disability backgrounds.

What are the barriers and enablers in leadership development?

Barriers and enablers are often a mirror of one another. This means that in discussions about barriers or challenges, an inverse approach is sometimes suggested as a way to enhance or improve access to, and the quality of, leadership development. In the New Zealand context, we’ve seen a range of barriers and enablers, including:

- Cost: Not only is leadership training sometimes costly for employees, it can also be costly for businesses. The costs for each include fees for such courses, time away from work and whānau commitments

- Location: Access to leadership training in remote areas is not always easy

- Recognising existing skills and knowledge and adapting to new settings; for example, migrants and refugees in particular may have developed skills, knowledge, and networks to have thrived in leadership positions overseas may need support or a pathway to recognise and grow the equivalent in Aotearoa

- Under-representation: This applies to many communities: Māori, Pacific peoples, tāngata whaikaha, migrants, women, gender-diverse people, and others. People in these communities can feel like their values are excluded, face preconceptions about their abilities, or experience contradictory attitudes.

- We found that Pacific people face a range of barriers which may be extrinsic (such as facing negative stereotypes and a feeling of tokenism) or intrinsic (such as navigating cultural norms around humility, and multiple accountabilities)

Where to from here?

Te Manu Arataki Leadership Project focuses on generic leadership skills that every industry can benefit from. It is considering whether existing leadership training products are fit for purpose, developing generic leadership products that are universally applicable where appropriate, and helping with career pathways to leadership.

The findings from this research are helping to guide our engagements in Te Manu Arataki project and decisions about leadership qualifications and wider workforce development initiatives; including the challenges and opportunities to be mindful of.

If you would like to contribute to our project please sign up to be part of the consultation group.

A list of the material that has informed our environmental scan is here