For many people and businesses within the Service sector, the past two years have been incredibly challenging. It is more important than ever before for businesses to actively focus on their workforce.

We are proud to share the findings of our research about resilience and mobility in the Service sector, against the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, and with a focus on Māori views and experiences.

You will experience the Service sector in action every day. Whether it’s when you’re out shopping, contacting your utilities company, sharing a meal out with friends, seeking financial advice as you prepare to buy a new home, or heading away on a well-deserved holiday. The Service sector is wide-ranging.

It is also likely that you have worked in the Service sector as well – two out of every three people will work in the Service sector at some point in their lives.

The Service sector includes at least:

“Understanding that Tourism gives us an opportunity to share our stories, the stories that are ours. We need to build this culture.”

(Tourism, Māori SME)

“Created the business to empower the mana of wahine.”

(Retail, Māori SME)

I’m in it to work to meet the needs of struggling whānau.”

(Food & wholesale, Māori SME)

There are many dimensions to resilience and mobility, and often they intertwine. By understanding these dimensions and identifying and acting on ways to enhance them, we think that the Service sector will be well placed to continue adapting and thriving well into the future.

Connections – whether that’s through relationships or networks – strengthen people across workforces, businesses, and the wider sector. These connections are invaluable pathways for businesses to access practical and financial support for a range of areas within their business, from employees, to mentors, to childcare. Although the nature of relationships and networks can differ, they provide a web of support around individuals within the Sector. This helps to buffer against issues such as staff shortages, increase wellbeing, and bring in opportunities for employees and businesses to grow skills and collaborate.

“We are linked in with our waka ama club and support our rangatahi programmes within the club. We are able to bring on trainees and create pathways for our rangatahi to come into our business.”

(Tourism, Māori SME)

Networks speak to the less personal relationships between workers and businesses, or between businesses and industries. Although these networks could draw on personal relationships, they tend to sit at the more ‘transactional’ end of interactions. These networks hold broader connections between businesses and workers that help tap into worker pipelines.

We’ve heard that sometimes an absence of networks challenges people’s resilience. Although there is some business support available, there is a desire for information, connections, and support that is created from, or reflects, Māori perspectives.

“How do we find business support that is te ao Māori and kaupapa Māori orientated? There’s nothing in the mainstream/commercial space that works for us as Māori”

(Tourism, Māori SME)

“We know what our business needs, being able to have a mentor, or someone who understands from a kaupapa Māori perspective. It needs to be tailored to the business, not a cut and paste copy.”

(Retail, Māori SME)

“We do a fair bit of staff sharing through businesses. So it’s helpful if we can top up the amount of hours and the other Cafe because it’s quite quiet. They come and do a day here or one at the restaurant”. (Food & wholesale, Māori SME)

A deep purpose and long-term horizons are crucial for Māori in the Service sector. It’s from this foundation, that financial sustainability will come.

There are signs that Māori-owned businesses have a commercial advantage in some cases. The profit margin for Māori-owned businesses in the Travel Services and Contact Centres & Industry Support Services industries is at least 10% higher than that of non-Māori-owned businesses in the same industries.

We heard from Māori in the Service sector that the purpose and drive behind their mahi was deeply intertwined with their Māoritanga and often provided the foundations for what they defined as resilience. These values are demonstrated in a range of ways, such as the desire to provide employment opportunities for rangatahi and whānau, to find creative ways to keep people employed in times of adversity, to showcase their culture to others, and to express themselves through their product.

These values are demonstrated in a range of ways, such as the desire to provide employment opportunities for rangatahi and whānau, to find creative ways to keep people employed in times of adversity, to showcase their culture to others, and to express themselves through their product.

“It is in our DNA as Māori to naturally be business and resilience minded, we build up to this and add to our character.”

(Tourism, Iwi-owned)

“The CEO gave up some of his own pay so that we could top up our staff because less hours means less money. He was topping up everyone’s pay so that they were all getting the same as before”

(Retail, Māori SME)

“As Māori we get in and we do it. We think for the long term because who will make them if I don’t? That’s resilience. It’s not about economic gain. It doesn’t matter what the service or product, the resilience comes from the deeper te ao Māori meaning. It’s more to do with the kaupapa, as the mother of it, and you want to see it reach its potential.”

(Tourism, Māori owned SME)

Iwi businesses emphasise the importance of leaving a legacy of better outcomes for generations to come. The businesses can vary but their purpose is the same; to bring benefits to their descendants through cultural, social or financial success.

Having a deeper purpose behind working in the Service sector may underpin people’s work while they are in it. It will likely influence the decision they make if they move within or beyond our sector.

We have an obligation much higher than a mum and dad business, the legacy that we must uphold, and hand down is much bigger.”

(Tourism, Iwi-owned)

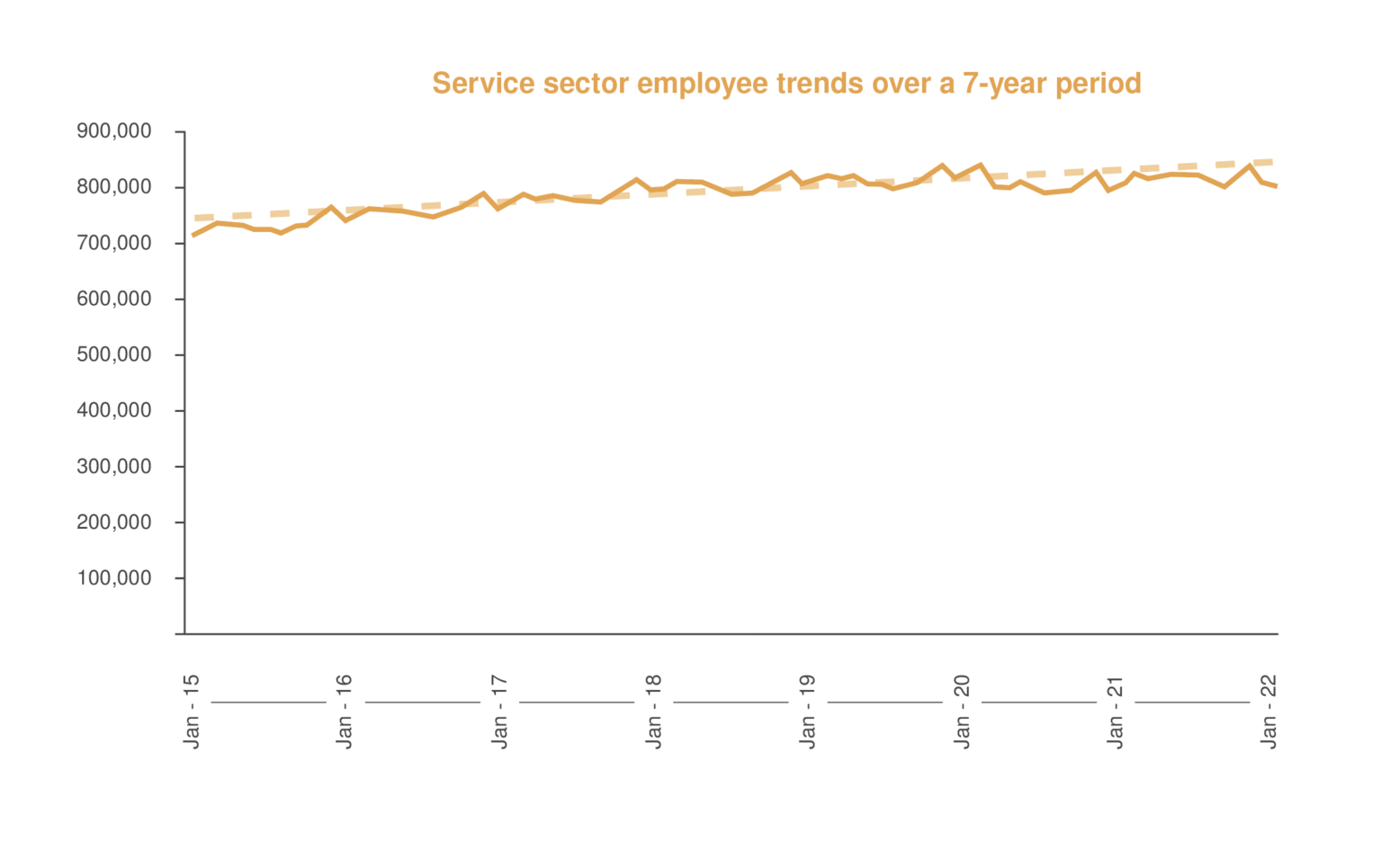

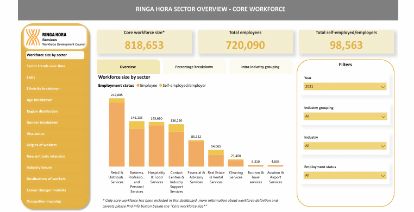

The overall size of the Service sector workforce is relatively stable, however the people in it are changing regularly.

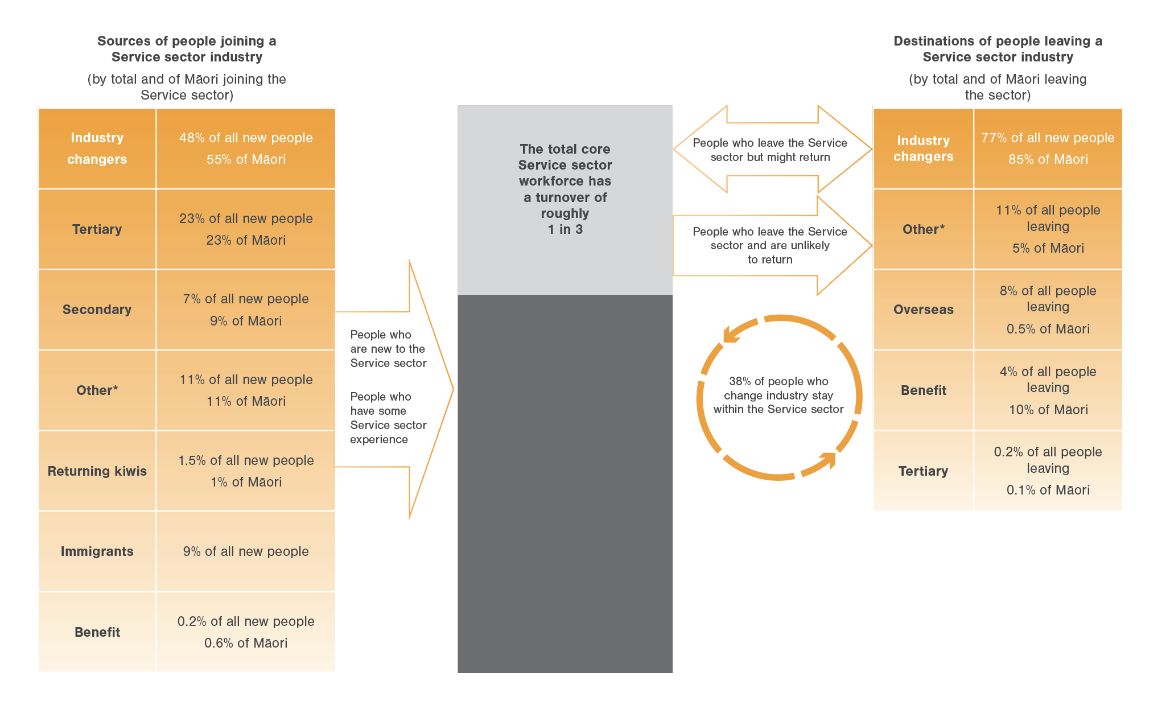

Our research confirms the commonly held perception that people who are in their first, temporary, or seasonal jobs are highly mobile. These are people who would be counted in the non-conventional workforce. However, our research also highlights that mobility is a feature for the core workforce, where you might expect a higher degree of stability. The extent of movement is so amplified for the non-conventional workforce that combining them with the core workforce to provide a ‘total’ view would mean neither group is adequately represented. For these reasons, in this section we’ve focused on sharing a picture of how mobile the core workforce is. More information is available about the non-conventional workforce in the accompanying full report prepared by Scarlatti.

The Māori workforce appears to have been hardest hit, particularly during the early stages of the pandemic (the second and third quarter of 2020).

At an industry level, Aviation & Airport and Hospitality & Food services were the most affected with border closures and lockdowns. The impact for these industries was swift and has been long-lasting, with numbers only just bouncing back now.

At an industry level, Aviation & Airport and Hospitality & Food services were the most affected with border closures and lockdowns. The impact for these industries was swift and has been long-lasting, with numbers only just bouncing back now.

“The issue we are having with the workforce now is the lack of people we have applying for these positions.”

(Food & Wholesale, Iwi-owned)

However, the large numbers of employees who did lose their jobs demonstrated their resilience through their ability to pivot. In 2020, roughly 80% of the people who left the sector (voluntarily or involuntarily) transitioned into another industry. A similar proportion of people managed to transition into a new job within three months.

Employees shared that being an “all-rounder” enables more employment opportunities within the sector. Some employers could leverage off the wider sector churn, paired with the ability to provide on the job training, to fill their own workforce needs.

“We started linking up with other companies like Air NZ to recruit, being their loaders, baggage handlers and anyone that kind of fit the security profile.”

(Security, Auckland)

“Some roles have been left open for a very, very long time. And it was five to six weeks plus we still haven’t had anyone.”

(Retail, Queenstown)

“A lot of our teams are tired, management roles have had to work quite operationally, we have had a lot of sickness, not just COVID so our workforce is exhausted.”

(Tourism, Rotorua)

Overall, the long-term trends of employment numbers stayed undisturbed. As restrictions were eased, Māori employment numbers in the Service sector also returned to pre-pandemic levels. The Māori workforce size in the Service sector has seen the biggest growth in 2021 over all other ethnic groups.

At the same time, employers shared that staff shortages are an on-going major issue. Shortages that existed prior to COVID-19 have been exacerbated. The existing workforce is experiencing a strain or fatigue, and are also mindful of the risk that going to work may present to the health and wellbeing of their whānau.

Although the overall size of the workforce remains relatively steady over time, the composition of the workforce changes as people move in, around, and out of the Service sector.

We’ve looked at a cohort of new entrants to the Service sector (those who started in 2015) to identify when people are more likely to leave the Service sector, as well as the characteristics of those who do.

Most people who move will find a new job quickly. 83% of the total workforce leavers took less than three months to transition into new employment.

Less than 10% of the people who left their Service sector job in 2020 took longer than 6 months to transition into new employment – whether in the Service sector or elsewhere. The only exception to this is the Travel workforce.

In some cases, the pandemic may have extended people’s tenure in the Service sector. However, it may be a short-term impact, and as we move out of the pandemic, the tendency towards movement is reappearing:

“Come 2021, we suddenly had people who had been with us for two or three years suddenly, who probably would have left earlier had COVID not happened, suddenly want to look at other opportunities, whether that be studying or different employers or moving out of town.”

(Retail and Cafe, Iwi-owned)

This movement may be shaped by people choosing what best suits their lives, or in response to a job loss from a shock such as COVID-19, or wider factors such as the availability of housing and transport.

“Often having a younger workforce tends to move off to the city at some point.”

(Food & Wholesale, Iwi-owned)

“Our fear is that if we identify a really good person, and we send them away for training [to] Hamilton or to Auckland, we might not get that person back. That’s a reality that we’re definitely dealing with at the moment.”

(Cafe, Iwi-owned)

“Employers have to really go out of their way to look at the whole person and what that person requires to keep them or attract them in the first place and then to keep them in. They’re different things to what they were previously. So, across the board, I think it’s really tough. The job at hand really is rolling with the new landscape.”

(Food & Wholesale, Māori SME)

The Service sector is an accessible option for many. Our research has shown that the demographic characteristics are largely representative of New Zealand in terms of age, gender, ethnicities and regional distribution.

If we took 10 people from the Service sector, over half would have a post school qualification, 5 of them would have come from a different industry or sector, and almost half would be over the age of 35. If we looked at where these 10 people lived, 5 would live in Auckland or Wellington, 2 would live in the South Island and the other 3 will be living in other North Island regions. The gender balance would be relatively even.

The mobile nature of the Service sector workforce is likely to contribute skills that are informed by a broad range of practices and places.

“We’ve got potential if we put the right skills and training in place to ensure we are growing [a] generation of SME people. Tourism is a natural fit for Māori”

(Tourism, Iwi-owned)

“Kids have become very device driven through forms of communication, and our service level has dropped considerably.”

(Tourism, Auckland)

So-called ‘soft skills’, such as customer service and communication are important in any business, but particularly for the Service sector where many roles involve hosting people.

For Māori, these skills are intertwined with their culture and their values, adding immense value to our Service sector industries.

The pandemic and wider changes in technology have impacted when and how people develop these skills. This highlights not only the value of these skills in the Service sector, but also the need to deliberately support their development and recognition.

An adaptive and responsive workforce that has a diversity of skills, knowledge, and attributes helps businesses to innovate during difficult periods.

People have shared examples of the efforts taken to maintain service and employment levels. For example, this includes having people cover multiple roles and wearing different hats in the business, working across different sites or even businesses if practicable, and shifting their focus away from international markets towards local communities. These practices were apparent regardless of the business size.

“Our big focus was trying to maintain meaningful work for our people and that meant upskilling our team so they have a significant degree of versatility.”

(Tourism, Iwi-owned)

A diverse workforce, with a breadth and depth of skills, also helps to mitigate the disruptive impact of turnover or churn by:

(Employee, Whakatane)

“Being older, enables you to have all the ground, entry-level skills needed to work in retail, hospo, and accommodation (cleaning) roles.”

(Employee, Whakatane)

Our research supports further exploration and action to enhance Service sector resilience and mobility

Ringa Hora will work with, alongside, or in support of industry, iwi, hapū, and Māori businesses, and other collaborators to enhance our collective understanding of the Service sector workforce and progress meaningful action. It is particularly important against the backdrop of the pandemic and as the Service sector continues to adjust to the challenges and opportunities that arise from a rapidly evolving environment.

For this kaupapa, we partnered with two organisations who bring mana and expertise to deliver high quality insights. Our research weaves together qualitative and quantitative information, and provides a local and national view of the Service sector. It has been undertaken with the support of funding from the Tertiary Education Commission.

Ringa Hora Services Workforce Development Council is one of six Workforce Development Councils established as part of the Reform of Vocational Education (RoVE). Our aim is to support the Service sector to tackle skill shortages, adjust to the future of work, build a strong skills base, and have the right training available at the right time.

Scarlatti is an evaluation and analytics firm, with over ten years’ experience undertaking quantitative analysis into the workforces of New Zealand. The team have a wealth of knowledge when it comes to using Statistics New Zealand’s Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI) and drawing out valuable insights.

Te Amokura Consultants specialise in policy, engagement, strategy, communications, and growing cultural competency through understanding Te Tiriti o Waitangi and a te ao Māori worldview. The team have a strong network of connections within Māori communities across the motu. Te Amokura exists to drive and provide better outcomes for Māori.